Digital technologies are renovating and disrupting traditional industries, changing business models, and delivering enormous productivity gains. But they’re also improving public service delivery including health and education needs, which are essential especially during COVID-19.

Digital transformation is a reality for the Palestinian territories of the West Bank and Gaza, where employment in the ICT industry almost doubled between 2008 and 2018, and digital development is among the national priorities.

However, the Government of Israel has imposed many restrictions; and these are among the biggest impediments to the development of the digital sector and thus to the development of economy and society. These measures have a highly negative impact on connectivity. Furthermore, pervasive movement restrictions hinder Palestinians’ private sector development, trade activities and job creation, with a major negative impact on the overall economic development.

Israel as a leading power in cybersecurity

According to a team of researchers from Harvard University, Israel ranks 11th among the most powerful cyber countries in the world in 2020. Despite this, the country is considered one of the most developed in the world for cyber activities. Commentators justify its not-on-top position asserting that analysts depend on open-source data for their research, whereas much of Israel’s cyber power is operated covertly, limiting their analysis.

Cybersecurity and digitalization: Israel and the Palestinian Authority

Cyber security strategies operate on the assumption that national cyberspace mirrors a country’s territorial sovereignty. The cyberspace is increasingly seen as an extension of its geographic space, and thus it’s increasingly perceived as an asset that needs to be protected. In a fragmented reality such as the one of the Occupied Palestinian territories, we can see how true this principle is: practices of territorial annexation, geographical occupation and blockade are paralleled in the cyber space. As declared in the art.36/3 of Oslo II Convention (1995), Palestinian Authority has the right to exert infrastructural autonomy in the digital sector; however, Israeli authorities currently control the Internet backbone and the infrastructural network, exceeding its legitimate territorial boundaries.

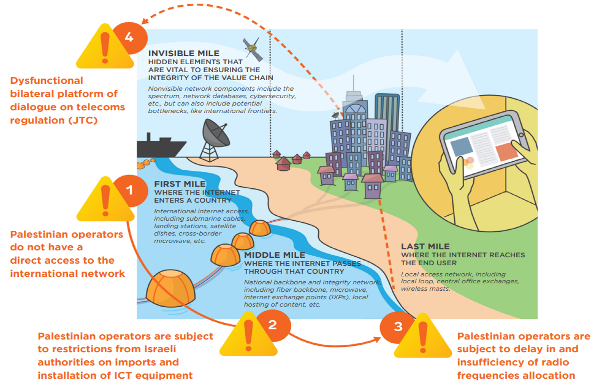

As shown in the picture below, the Israeli “digital annexation” unfolds through almost all the steps of the connectivity value chain that ensure an autonomous network.

First mile: where the internet enters a country

Palestinian operators need to go through Israeli companies to access international submarine cables. They aren’t allowed to own an international gateway to connect their network directly to the rest of the world; they are instead required to go through Israeli registered companies to carry traffic outside the West Bank and Gaza.

Middle mile: where the internet passes through the country

Bit-stream Service Access means that the incumbent installs a high speed access link to the customer’s premises, and makes it available to third parties. With bit-stream access, entrants do not have control over the physical line nor are they allowed to add other equipment limits. The commercial and technical freedom of Internet Service Providers is undermined; they struggle with the import of equipment, meaning delays in authorizations, cumbersome procedures, and extra costs due to the requirement to go through Israeli importers. Besides detaining full control on the core network, Israeli authorities regularly block the import of ICT equipment and technologies towards the Palestinian controlled areas of the West Bank, thus threatening the right to exert national sovereignty in cyberspace.

Last mile: where the internet reaches the end user

Fiber optic cable linking the main towns in the Gaza Strip and the cities in the West Bank have been installed. Microwave connection between the two transmission backbones in the West Bank and Gaza have been completed. But they quickly became saturated. With Oslo I (1993) granting Israel jurisdiction over Area C, Palestinian Internet operators require multiple authorizations for transporting or installing technologies in the area. Citing security concerns, the Israeli Civil Administration regularly turns them down. Meanwhile Israeli providers supply Internet connection and mobile services to illegal Jewish settlements in Area C. Over the years Israeli Internet Service Providers improved and expanded the infrastructural network to serve the growing settler community; this means that Palestinians in Area C need to roam on Israeli frequencies to access mobile Internet, commonly opting to subscribe to Israeli operators.

Invisible mile: hidden elements that are vital to ensuring the integrity of the value chain

Other key-but-invisible elements are compromising Palestine’ digitalization: in fact, as a result of Israeli policies, the bandwidth in Gaza is still limited to 2G. At the same time, Palestinians who can access Israeli providers due to geographic proximity can use 4G/LTE networks, undermining the competitiveness of Palestinian operators.

Further digital drawbacks after the May 2021 conflict

The armed conflict between Israel and Palestine erupted in May 2021 has exacerbated many socio-economic challenges faced by the Palestinians in Gaza. Besides civilian casualties, infrastructures (water, electricity, and internet networks) and aspects of everyday life (housing, education, health, and productive sectors) suffered from significant damage. All educational activities in Gaza were interrupted due to safety concerns and damages occurred to the facilities; electricity and internet connection disruptions became more frequent. Many office buildings (including offices of the IT companies and start-ups) and factories in Gaza’s industrial area have been damaged or destroyed. In addition, domestic factors such as lack of a sound regulatory framework and transparent competition regimes also hinder the sector’s development.

The new Telecommunications Law was adopted on October 2, 2021, but it still remains to be implemented.

SILVIA PIZZIGONI