As water is fundamental for health, hygiene and nutrition, it’s also one of the main contended assets when shared by neighboring regions; if regulations are iniquitous, tensions may arise. Several conflicts are being fueled by competition for dwindling natural resources. Middle East and North Africa are the main regions in the world where water-related conflicts happen, and the Palestinian conflict is one of these.

Water: building bridges or source of conflicts?

Water grabbing is the distribution of water resources in a way that leaves one or more parties feeling the distribution is less equitable. Since water is an asset of primary importance for health, hygiene and nutrition, the basis of life, water scarcity and allocations may become a source of conflict between involved parties.

This situation has been well developed and formalized in the Dr. Homer-Dixon theory, a model of the relationship between the scarcity of renewable resources – such as water and soil – and the outbreak of violent conflict within countries concerned. The model describes how an environmental scarcity contributes to certain destabilizing social effects that make violent conflict more likely.

In 1968, the over-exploitation of a natural shared-common-pool resource was named “Tragedy of the Commons” by Garret Hardin in Science Magazine, to indicate how emblematic and problematic the consequences of such situation can be.

The term ”Hydro-politics” first coined by Waterbury in 1979 describes how inter-state politics can be extremely connected to the management of shared water resources. Water is a resource but it can become a weapon to enforce a political agenda, and this is a global concern for peacebuilding; hence, understanding hydro-politics is essential to analyse, predict and study water-based conflict scenarios between riparian countries.

“The human right to water is indispensable for leading a life in human dignity”

UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, General Comment No. 15, para 1

Water involvement in intrastate and interstate conflicts: Middle East and North Africa

A study published in 2020 reported that among the reviewed publications regarding water in conflict-affected countries from 1992 to 2019, there is a clear geographic focus on the Middle East, followed by Africa, and Asia.

Once referred to as “The Fertile Crescent,” the arid region also called MENA (Middle east and North Africa) is still facing many issues regarding water scarcity, allocation and the related political conflict over claims to water resources. Meanwhile water is being withdrawn at alarming rates, leading to alerts on the environmental side as well. There are hundreds of episodes in the last decade where water has been involved in Middle East conflicts. The destruction of water infrastructure remains a widespread characteristic of the conflicts in the Middle East.

The role of water in conflicts falls within three categories:

- water as a weapon (polluting water, disrupting supply, monopoly of water sources…)

- water as a target (chemical contamination, damage to water supply networks..)

- hybrid cases: water can be involved as a strategy.

Among all water-related or water-involving conflicts in the Middle East, the most notable are: Lebanon with Syria and Israel, Turkey with Syria and Iraq, Egypt with Ethiopia, India with Pakistan, Cameroon with Chad, and Kenya with Somalia.

Palestine: the beginning of a water conflict

The struggle for water has been at the centre of many tensions between countries in the region. The Israeli-Palestinian conflict is a clear example of Weaponization of Water. This water conflict dates back to the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, and escalated in 1967, when Israel occupied the WB and GS. That’s when Israel began the control and exploitation of the water resources in the Palestinian territories. That same year the Israeli authorities issued the Military Order 158, which forbade Palestinians from building new water installations without a permit from the Israeli army.

In 1982 Mekorot, the government company operating under the Israeli Ministry of Energy and the Water Authority, assumed ownership of all West Bank water supply systems.

The problem further escalated in the 1990s, when Palestinians and Israelis began to negotiate the Oslo Accords and established the PA. Israel kept progressively controlling and exploiting major water resources in the region.

“Whiskey is for drinking, water is for fighting over”

Marks Twain, American Writer (1835 –1910)

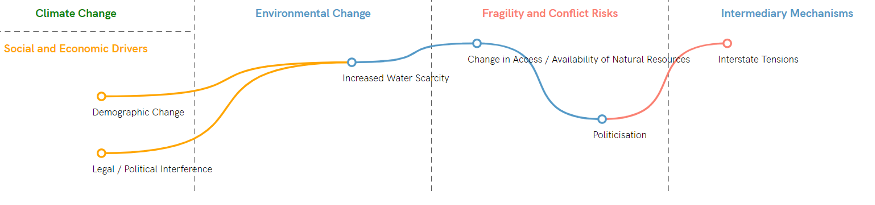

In a website dedicated to climate diplomacy, the water grabbing conflict in Palestine is explained with the auxilium of a conceptual model, shown below. Environmental changes (water scarcity) are shown in the second column, and have direct social (yellow lines) and/or climatic causes (green lines), both of which are displayed in the first column. These changes have consequences for societies (third column) that translate into conflicts and fragility risks (last column).

Palestine: current unbalanced water allocation

There are a few main obstacles for a fair and easy management of water for Palestinian Authorities. The JWC (Joint Water Committee), established within the Oslo Accords to develop and manage Palestinian water resources and services through accords between Israeli and Palestinians, proved to be ineffective and incapable of proceeding with drilling projects since Israel posed vetoes on many Palestinian proposals. This lead to a stagnation of JWC aims and advancement since the Palestinian Authority (PA) withdrew from the JWC for nearly a decade.

Water quotas from water pipes are assigned to Palestinians, while for Israeli the water supply goes along with the demand. Water issue is addressed in the article 40 of Water Oslo Accords; in accordance with the article “approximately 80 percent of the waters pumped from the aquifers were allocated for Israeli use, and the remaining 20 percent for Palestinian use.”

Several procurement difficulties are encountered when the reception of components for water plants derives from export (pumps, valves, etc.). The price for Palestinians is 400 percent of a normal water bill. And often, water supply is interrupted because of military exercises, which are announced abruptly.

Palestine: complementary causes involved in water supply shortage

There are two main water sources for Palestinians: aquifers and Jordan river. Aquifer water can be accessed through water wells or through natural springs. The main aquifers are the Coastal Aquifer – with Israel upstream and Gaza downstream – and the Mountain aquifer, which starts in the heights of the West Bank and flows to the Jordan Valley.

Rainfall collection basins and aquifers are quite free-access point of water for Palestinians. However, 96% of aquifers contain non-potable water. For example, Gaza’s only fresh water resource, the Coastal Aquifer, is insufficient for the needs of the population and is being increasingly depleted by over-extraction and contaminated by sewage and seawater infiltration.

Water pipes that allow the transmission and distribution of water often date back to the Transjordan era: aging and poor maintenance for water plants and distributions lines cause yearly losses.

Electricity is a requirement in order to operate water infrastructures such as wastewater processing, water stations and desalination plants. In Gaza, severe electricity shortages have significantly affected the functionality of the existing infrastructure and the population’s access to clean water.

The population growth, over the years, is making this problem more and more relevant. Water demands grow and urban populations in the Occupied Palestinian Territory have nearly tripled in the past 25 years, contributing to a reduction of local groundwater recharge. Palestinians have access to only 14 percent of the basin’s resources. Each Palestinian has on average 70 litres per day in contrast to 280 liters on average for an Israeli. WHO’s threshold for a healthy life is 100 liters, but each Palestinian, on average, has access to 70 liters per day, in contrast to the 280 liters accessible for an Israeli.

Silvia Pizzigoni